(8 May 2014: I’ve let this slide since the initial flurry of stories. My one update is something of a meta-update: Wechsler and Koppelman have their own page of links to press stories and interviews here. There’s at least one radio interview there that I haven’t included here.)

(26 April 2014: I’ve added below a follow-up story from Mark Tewfik that includes some additional personal background on Dan Wechsler and more on the Baret; I’ve also gotten confirmation that Koppelman and Wechsler did not present anything about the Baret at any conferences prior to their announcement on April 21. I’m leaving town for a couple days but hope sometime next week to organize all these resources in a somewhat more intuitive way, if only to indulge my own blessed rage for order.)

(24 April 2014: Not much new analysis or news today as the media cycle seems to spin out; scroll down to see where I’ve added another story from Forbes by Nathan Raab of the Raab Collection, and a link to a radio interview with Wechsler on WNYC. Thanks are due to colleague Don Lindgren of Rabelais Books, who has been sharing related stories and links that I might otherwise have missed.)

(23 April 2014: There have been a few updates as the story spreads through the media but not much new analysis that I’ve found. Scroll down to this morning’s update at 8:30am EDT about the TLS blog for everything I’ve thought worth collecting over the course of the day.)

(22 April 2014: I have tried to continue to update this post as new stories come out; there is a rough chronological order to the updates, though when the updates come from the same source — say the Folger Library — I tend to group them together. I may not include all stories that simply repeat or revist the news of the announcement unless in a few instances it strikes me as curious that the story was relayed non-critically, viz. BoingBoing.)

On April 21, 2014, news broke that booksellers George Koppelman of Cultured Oyster Books and Daniel Wechsler of Sanctuary Books (both in New York), “believe they have found William Shakespeare’s annotated dictionary.”

(That apt summation from an article by Mark Tewfik, a bookseller in New York associated with Maggs Brothers, which appeared in Australia’s The Age. Tewfik’s article also appears in the Sydney Morning Herald of April 21, 2014. At some point when I’m not pulling this stuff together, I will figure out the interlocking directories of Australian journalism.)

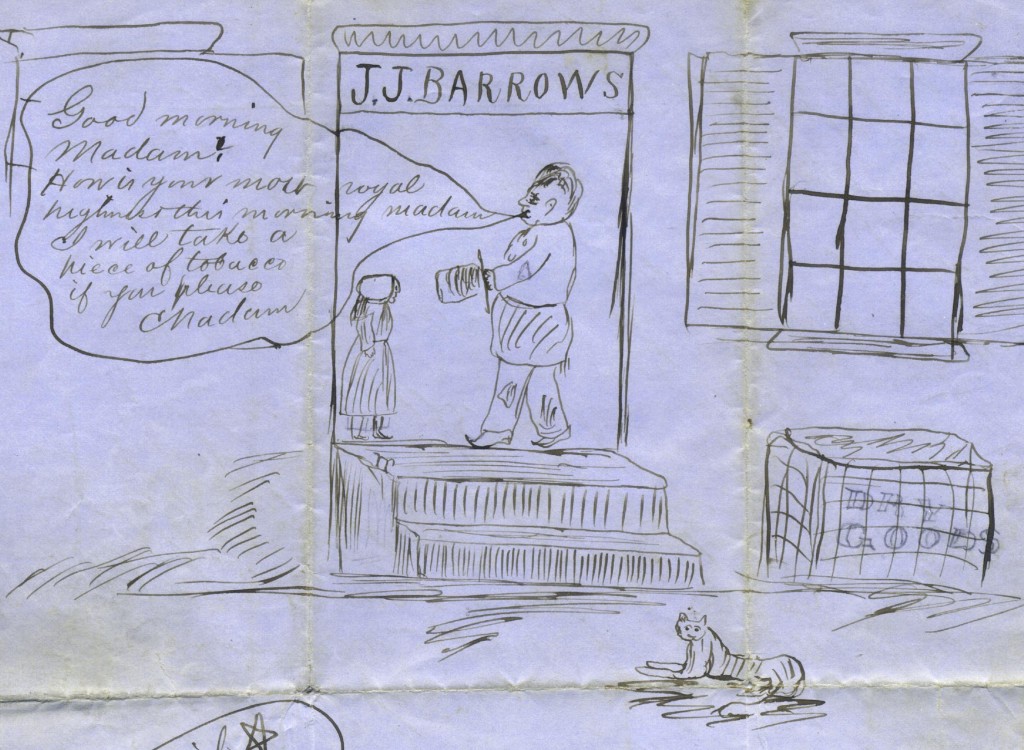

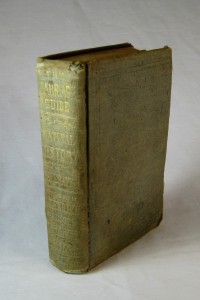

The book in question is an annotated copy of Alvearie or quadruple dictionarie (London, 1580) by John Baret. I assume this is STC 1411, see the catalog entry for a copy of this title at Oxford here.

Koppelman and Wechsler make the case in their book Shakespeare’s Beehive (New York, Axeltree Books, 2014), available here. (You can also register for free at their website to view scans of all the annotations.)

Bookseller and author Henry Wessells has published an extensive review of Shakespeare’s Beehive here. (Updated 9:40am EDT 23 April 2014 to correct the spelling of Wessells’s surname after having received a very polite note from the man himself.)

Adam Gopnik writes in “The Poet’s Hand” about Koppelman, Wechsler, the annotated dictionary, and more broadly about the fascination with Shakespeare relics in the April 28, 2014 issue of the New Yorker (subscription required): “If a movie were made of their quest for Shakespeare, Koppelman would be played by Wallace Shawn, Wechsler by Paul Giamatti.”

(Updated on 23 April 2014 to correct the publication date on the Gopnik piece from the mistyped April 28, 2104, which may have been my unconscious admission of the persistence of Bardolatry. Dates are of course easy to transpose; I will note that as of 7:45am the headline to the account of the announcement by Julia Fleishacker published here on 23 April 2014 on the Melville House Press blog inadvertently gives the Baret publication date as 1850. There is many a slip twixt coffee cup and lip, figuratively speaking, at least when I’m updating this thing in the morning.)

The French site ActuaLitté published an article dated 21 avril 2014, with a nice photo of the “word salad” on the rear blank.

(Added at 3:40pm) Sunday Steinkirchner of B&B Rare Books publishes a nice summary of the Koppelman-Wechsler announcement at the ABAA blog here, and an earlier note about the announcement at her blog at Forbes, here.

As of this writing (9:30am, EDT), Dan De Simone, the recently-appointed Folger Librarian at the Folger Shakespeare Library has, per the Tewfik article, promised an official statement on the dictionary. I’ll update as new relevant links come to light. These links have been cobbled together with some haste and I’ll try to add and/or correct and amplify for my own reference.

10:15am, EDT, updated to add a 8:33am tweet from Sarah Werner at the Folger:

@john_overholt @JackLynch000 @PeterSokolowski Stay tuned for a @FolgerResearch blog post on this!

— Sarah Werner (@wynkenhimself) April 21, 2014

The Folger Research Blog is here. (My abilities to link to tweets is rudimentary and evolving.) The Folger’s page of “Current Press Releases” is here. (As of 11:24am, the most recent Folger press release is dated April 2, 2014.)

Updated 4pm EDT — the Folger research blog article is up here.

Folger Library Director Michael Witmore and Curator Heather Wolfe write (in part):

At this point, we as individual scholars feel that it is premature to join Koppelman and Wechsler in what they have described as their “leap of faith.” Having ourselves worked extensively with collection materials and digital corpora, we have written this blog post in order to highlight research methods that we expect will be used to evaluate Koppelman and Wechsler’s claims. Regardless of the identity of the annotator, the book that Koppelman and Wechsler (hereafter K&W) have turned up is fascinating. . . .

What is new or controversial about K&W’s claim? They are not simply saying that Shakespeare consulted Baret’s Alvearie at some point in his life. As they note in their study, T. W. Baldwin made this argument some time ago, with real success. We know that Shakespeare and other early modern writers used source books like the Alvearie to fire the imagination. Shakespeare’s fascination with proverbs in his plays, for example, can be traced back to some of the printed proverb collections that were becoming popular in the sixteenth century. As the lexicographer John Considine has demonstrated, dictionaries were an important source of proverbs during this period, since they offered up proverbial sayings to illustrate the meanings of words.2 We should not be surprised, then, to learn that Shakespeare read and perhaps was influenced by a book such as Baret’s Alvearie: it supplied him with a trove of sayings, associations, and conceits that many writers trained in the humanist tradition would have been keen to mine for their own texts.

What is new here is the idea that a particular copy of Baret was annotated by Shakespeare and that his annotations are distinctive enough to provide (1) a paleographic link with other known examples of Shakespeare’s handwriting and (2) a kind of associative map to verbal patterns in Shakespeare’s poems and plays.

(See their full blog post for citations.)

(Update at 1:30pm) Professor Grace Ioppolo, FSA, of the University of Reading, tweets her critical observations on the Koppelman-Wechsler Baret. (Ioppolo and Peter Beal are editors of Elizabeth I and the Culture of Writing, British Library Publishing, 2007. See a list of Ioppolo’s publications here. Dr. Peter Beal, FBA, FSA is a Senior Research Fellow at the Institute of English Studies at the School of Advanced Study, University of London.) Because I am still figuring out how to use Storify and was somewhat in haste, I inadvertently left out one of Ioppolo’s relevant tweets.

(Updated 9:45pm) Dr. Jason Scott-Warren of Gonville & Caius at Cambridge and the Centre for Material Texts writes “There is absolutely no reason to believe that Shakespeare was the annotator of the volume.” His blog entry, which touches on the practice of dictionary annotation, is here.

(Updated 9am, 22 April 2014) Aaron Pratt, a PhD candidate in English literature at Yale, here addresses the question of the “Bucke-bacquet” and the powers of wishful thinking, significant figures, and how the Shakespeare cult might be credited with an interesting discovery in any event–whatever the final consensus might be on the Koppelman-Wechsler Baret.

(Pratt also has a foot in the bookselling world, and in the interests of full disclosure I think I should admit that I once sold him a chapbook for a trifling sum.)

(Updated 10:15am, 22 April 2014) Robinson Meyer of The Atlantic publishes this morning a good general summary of the announcement and critical reaction here. Here concludes with a brief meditation on the role of technology, information and print culture:

As scholars debate and discuss the question, they’ll do so in writing, a kind of additional marginalia to the Alvearie’s scribble. And they’ll be helped by the considerable resources placed online by Koppelman and Wechsler, like high-quality scans of the whole book. The sites themselves, and the openness of the scans, seem to make our incredible new information technology worthy of an earlier era’s: Shakespeare had his own new IT, a thriving print culture that was just coming into existence.

(Updated 2pm EDT, 22 April 2014) Cory Doctorow supplies this morning on BoingBoing a fairly uncritical report of the Koppelman-Wechsler Baret here.

(Updated 2:30pm EDT, 22 April 2014) Andrew S. Keener, “a Ph.D. student in English Renaissance Literature at Northwestern University and a casual book collector,” publishes today on his blog a generous and informative piece here, “Not Shakespeare’s Beehive? Doesn’t Really Matter.”

Keener’s piece lays out some of the context of John Baret’s Alvearie (Keener notes, “in recent years I’ve consulted a few hundred copies of books designed for students of Renaissance language, Baret among them”) and explains some of the history of reader annotations and Renaissance dictionaries: “So, if we stop worrying about Shakespeare, Koppelman and Wechsler’s copy of the Alvearie can tell us something useful about the relationship between language-learning and book use in the Renaissance.”

(Updated 8:30am EDT, 23 April 2014) The TLS Blog has an entry “Shakespeare at 450” by Michael Caines posted on 22 April 2014 here. After surveying celebrations ranging from Shakespeare’s Globe “hosting a series of lectures by distinguished Shakespearean scholars” to “the V&A’s (ahem) Cakespeare competition, which has its own Pinterest page,” Caines notes,

And of the potentially controversial announcement of the discovery of Shakespeare’s annotated copy of John Baret’s Alvearie, or Quadruple Dictionarie, there will be more later – for now, let’s just note that among the earliest to take gleeful note of the claims of George Koppelman and Dan Wechsler is Forbes.com, for whom there are generally applicable lessons for entrepreneurship here: “here’s how a great find or new invention within your industry can impact your business”. It beats waiting 400 years, I suppose.

(Updated 10:40am EDT, 23 April 2014) Colleague Dan Dwyer of Johnnycake Books says this morning (in a note on an ABAA bookseller listserv) that he will have Dan Wechsler of Sanctuary Books–the co-author of Shakespeare’s Beehive–as a guest on his radio show “This Old Book,” this Friday, 25 April 2014 at 12:30pm EDT.

You will be able to livestream the interview on Robin Hood Radio (“The Smallest NPR Station in the Nation”) here (though be warned the site begins streaming audio automatically when you click through). After the show airs, you will be able to find the podcast here (no direct link to the show seems easily made, scroll down the sidebar “Browse Our Shows,” click on “This Old Book with Dan Dwyer.”)

Dan is a good guy, you may have see him mentioned as the bookseller offering a pair of Eugene O’Neill’s underpants for sale.

(Update 2:30pm EDT, 23 April 2014) Lots of media coverage, none on first glance seeming to add much new to the conversation but this gives some idea of the scope of this story:

Alison Flood posts on the Guardian, “Shakespeare’s dictionary is a possibility that makes me look up,” here.

Lizzie Parry publishes here a piece in The Daily Mail, “Was Shakespeare’s dictionary discovered on eBay?” (After a cursory glance, I will have to cast my loyalties to the book trade aside and note that my favorite Lizzie Parry piece is the wonderfully headlined “Britain’s most bizarre insurance claims include damage caused by a BADGER locked in a shed and a baby vomiting on a laptop during a Skype call.”)

Per this tweet, the BBC News Hour interviewed Koppelman and Wechsler. (I’ll see if I can dig up an archived version as the day passes.)

The CBC Books page posts this story today, “Have we found Shakespeare’s dictionary?” The story includes an audio link to the interview on 22 April 2014 with George Koppelman on the CBC radio show As It Happens.

(Updated 3:15pm EDT, 23 April 2014) Because I’ve always wanted to put the meta- into Metafilter, an entry on MeFi today here notes the Koppelman-Weschsler annoucement (and throws a link to this compilation). One commenter on that entry recounts this tantalizing story,

I have some hazy memories of being in a hotel bar a couple of weeks ago and listening to a couple of academics talking about this. Story was, these guys had a paper accepted for a seminar on manuscript studies at one of the big conferences in Renaissance studies recently. They ignored the theme of the seminar and presented their evidence for this instead. Then the other seminar participants started pointing out how pretty much all of their conclusions relied upon basic misreadings of Elizabethan secretary hand and it became very awkward.

If anyone feels like chasing that story down, I’d be grateful. As the Bard himself might have written, to independently verify this story might make it at least once heard and thrice-meta.

(Updated noon, 24 April 2014) One colleague close to this story tells me that Koppelman and Wechsler kept the story of the Baret quiet, and that aside from a few friends and colleagues, and the scholars with whom they had consulted, they had made no public announcements or presentations. (Update 26 April 2014: I have confirmed that Wechseler and Koppelman did NOT make any conference presentations prior to the announcement on April 21.) Does the MeFi comment above conflate another recent supposed Shakespeare discovery?

(Updated 6:45pm, EDT on 23 April 2014) Jennifer Howard writes about the Koppelman-Wechsler Baret in the Chronicle of Higher Education piece “Shakespeare’s Dictionary? Skepticism Abounds,” here. Her piece falls into the camp that despite the skepticism of scholars–or perhaps because of the skepticism–the piece deserves more and closer study.

(Updated noon, EDT, 24 April 2014) Nathan Raab of the Raab Collection (an A.B.A.A. member) has published at Forbes here a good general look at the case of the Koppelman-Wechsler Baret, including reactions from scholar David Scott Kastan at Yale, and follow-up reactions from Witmore and Wolfe at the Folger.

(Updated 6:30pm EDT, 24 April 2014) There was a radio interview today with Dan Wechsler on WNYC in New York. The audio is available here.

(Updated 1:30pm EDT, 26 April 2014) I’ve added a follow-up story from Mark Tewfik dated published in Australia’s The Age on April 26 with more of a personal profile of Dan Wechsler here.

***

Whether or not a scholarly consensus builds around whether or not this is Shakespeare’s annotated copy, this is a fine example of booksellers doing work: making an investment in money, time, and resources based on prior experience, taste, and scholarship. As an investment of $4000-$5000 cost up front with a huge potential upside, there’s a lot to be said from a bookselling angle (and with the 450th anniversary of Shakespeare’s birth hard upon us) for them at least pressing the case. This copy of the Baret has now become this copy of the Baret.

(I’ve done none of the reading yet, you might best categorize me as a skeptical agnostic on whether this is the Bard’s own copy. In any case, I’m hoping this will not simply be a nine days’ wonder.)

(Updated on 22 April 2014) I’ve started some of the reading. Questions of skepticism have been much on my mind, and the exercise of maintaining critical openness has been salutary.

One bookseller has remarked in another forum on the role of faith in bookselling and whether booksellers should be held to a higher standard of evidence. The question of how much evidence a bookseller needs before forging ahead with their material makes me recall A. J. Liebling’s sketch of the carnival impresarios Joe Rogers and Lew Dufour, “Masters of the Midway,” and the duo’s career as “practical ethnologists” running the “Darkest Africa” concession at the Century of Progress World’s Fair in Chicago in 1933-1934:

By the time Dufour got back to Chicago with his company of hamburger-eating cannibals, Rogers had built the village, a kind of stockade containing thatched huts and a bar. ‘We had a lot of genuine junk, spears and things like that, that an explorer had brought back from the bacteria of Africa,’ Joe Rogers says, ‘but this chump had gone back to Africa, so we did not know exactly which things belonged to which tribes–Dahomeys and Ashantis and Zulus and things like that. Somehow our natives didn’t seem to know, either.’ This failed to stump the partners. They divided the stuff among the representatives of the various tribal groups they had assembled and invited the anthropology departments of the Universities of Chicago and Illinois to see their show. Every time an anthropologist dropped in, the firm would get a beef. The scientist would complain that the Senegalese was carrying a Zulu shield, and Lew or Joe would thank him and pretend to be abashed. Then they would change the shield. ‘By August,’ Joe says with simple pride, ‘everything in the joint was in perfect order.

The only firm conclusion I’ve drawn during this flurry of controversy would be my conviction that the promiscuous use of the old medical saw about hoofbeats (and the likelihood of zebras vs. horses) be flagged and/or flogged until we are no longer troubled by its smug ubiquity. The phrase to me suggests that final party guest who will not go home until he has made his point about campaign finance reform; you may be in agreement with his argument but you wish he might retire.

Perhaps an appropriate or more generous aphorism drawn from medical practice sits waiting somewhere, say in Browne’s Hydriotaphia–like “Sense endureth no extremities, and sorrows destroy us or themselves” (Chapter V), or even from Browne’s Letter to a Friend,

Owe not thy Humility unto Humiliation by Adversity, but look humbly down in that State when others look upward upon thee: be patient in the Age of Pride and days of Will and Impatiency, when Men live but by Intervals of Reason, under the Sovereignty of Humor and Passion, when ’tis in the Power of every one to transform thee out of they self, and put thee into the short Madness.

But I wander from the point (and one might in good conscience suggest that I have myself succumbed to the temptations of my humors and passions).