The stark warning of the propaganda cartoon in a 1916 issue of the Chicago Board of Health’s bulletin Clean Living was clear enough, showing as it did a householder putting screens up on his window mere moments in advance of an apocalyptic swarm of house flies issuing forth from his own garbage pails, the whole lurid domestic scene playing out under the bold legend, “Our Greatest Menace is Domestic Not Foreign!” The Progressive Era of course saw many reforms in public health–the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906 is probably the best known–but little remarked upon today is the era’s war against the fly.

It’s probably impossible to imagine the amount of horse manure and outhouse ordure and general rotting garbage that beset American towns and cities at the turn of the 20th century, but by all accounts it was considerable. Flies were of course a part of that landscape and by the late 19th century it was pretty well established that these pests were a vector for all sorts of ills, and thus did stamping out the fly became a chief concern of all right-thinking public health experts. (Utah’s state health commissioner Dr. Theodore B. Beatty apparently did much to make “Swat the fly!” a common greeting.)

Into this affray stepped Alonzo E. Chapman.

On December 11, 1913, the Redlands, California, inventor submitted his patent application for his “Knockdown Fly-Trap,” which he of course claimed was both novel and useful, adding, “[my] invention relates to fly traps, being more particularly of the type of fly trap which is placed out of doors adjacent buildings, the trap having capacity to hold a large quantity of flies.”

On December 11, 1913, the Redlands, California, inventor submitted his patent application for his “Knockdown Fly-Trap,” which he of course claimed was both novel and useful, adding, “[my] invention relates to fly traps, being more particularly of the type of fly trap which is placed out of doors adjacent buildings, the trap having capacity to hold a large quantity of flies.”

(The “knockdown” aspect of Chapman’s device related to the trap’s portability rather than its fly-killing technique, relying instead on a cunning system of baits and screens.)

Chapman was hailed by the City Fathers of his hometown of Redlands, California, as something of a practical visionary hero, and he was made the city’s official city fly-catcher, a post he filled with admirable diligence in return for a weekly salary of $10 nine months out of the year; as the July, 1916 issue of Popular Science Monthly noted, Chapman and his traps were responsible for the capture of some 240-245 gallons of flies in one season–a mere 14,400,000-14,700,000 of the winged emissaries of death and destruction. As an admiring squib in the July 5, 1915 issue of The Detroiter pointed out,

Already much enthusiasm and interest in this city [i.e., Detroit] has been aroused by a ‘Swat the Fly’ campaign, and now some attention might be given to a ‘Trap the Fly’ campaign. Redlands’ experience was that despite the swatting, flies continued to thrive and make themselves a nuisance, and so this California city was one of the first in the country to carry on an organized, systematic campaign against the fly nuisance by the use of large size outdoor traps. In fact, to do this a special trap was designed and a new office was created, that of ‘Official Fly Catcher,’ and A. E. Chapman, the gentleman who stands in the photograph with the fly trap on the wall at his left is the ‘Official Fly Catcher’ of Redlands.

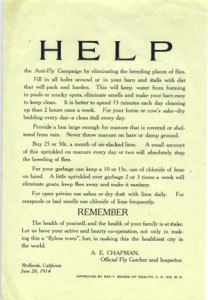

Chapman himself wrote an account of his efforts for the July, 1914 issue of American City, with hints to cities that might want to duplicate his success. As Chapman noted, “Cooperation has been the keynote of the methods used in Redlands,” and indeed his traps were not the only weapon in the anti-fly arsenal. As this handbill from Chapman (in his official capacity of fly-catcher) distributed to Redlands residents in 1914 notes, “The health of yourself, and the health of your family is at stake. Let us have your active and hearty co-operation, not only in making this a ‘flyless town’, but, in making this the healthiest city in the world.”

Little seems recalled of Chapman’s achievements, nor of his pioneering place in public health; he was happily at least possessed of a certain local renown–as the Popular Science article notes,

Mr. Chapman built a ‘jumbo’ trap, which he had in a ‘Made in Redlands’ day parade, inside of which are two small traps and a monster homemade fly.”

The fine handbill pictured here is an ephemeral relic of the Chapman anti-fly campaign, and has since been snapped up by a discerning institution; the description may still be of interest to some:

[Public Health]. Chapman, A[lonzo] E., Official Fly Catcher and Inspector. Anti-fly broadside, with the caption title “Help the Anti-Fly Campaign by eliminating the breeding places of flies.” Redlands, Calif.: Board of Health, 1914. Broadside, approx. 9 x 6 inches. First edition.

Urging Redlands residents to keep the fly population down by filling in holes, collecting manure, judicious use of lime, cleaning cesspools, etc. “REMEMBER. The health of yourself, and the health of your family is at stake. Let us have your active and hearty co-operation, no only in making this a ‘flyless town’, but, in making this the healthiest city in the world.” Chapman’s title–“Official Fly Catcher and Inspector”–is as given on the handbill and to judge from contemporary articles (cf. Popular Science Monthly and American City and County) Chapman the only official municipal fly catcher in the U.S., and his patent traps were erected around town with city sanction; his first year of operation, he eliminated some 245 gallons (or perhaps 14,000,000) flies. Chapman’s given name taken from his patent, 1136210. With the printed notice, “Approved by Sec’y. Board of Health, C. E. Ide, M. D.”