I get several calls a week from people who have old books. They want to know what the books might be worth and often they want to know whether I might want to buy them. I might get three or four fruitful calls over the course of a year and can offhand remember maybe three phone queries that yielded a mutually beneficial transaction of great scale (one collection of 17th century illustrated travel books, one nice little English popular medical book from 1653 that recommended rubbing your child’s tongue with honey and “salt of gem” to encourage a backward child to learn how to talk, and one American revolutionary book for which I am myself too backward and lazy to immediately recall).

But in general once the caller has with a few directed prompts begun to describe the books (broken sets of Stoddard’s lectures, Longfellow and/or Whittier reprints, “pretty good shape for their age,” etc.), I have usually made a referral and have cast about after a more productive use of my time.

So when I got a call yesterday from a woman who had been given my name by the librarian in a small town and who told me she had old books that had belonged to her late husband and she wanted to make sure that after she died her niece didn’t put them out at a yard sale for a quarter when they might in fact be worth more, I prepared my usual disclaimers. But before I could deploy the demurral genteel she steamrolled ahead with the anecdote of how her nephew had once borrowed a book from her for a book report and then later he was in Portland, Oregon and a bookseller out there told him the book was worth $1500 and in fact if it “hadn’t been a bootleg” the book would have been worth $100,000, but now the nephew was in Australia and no, she could not recall the title of that book but she had other books and those books were also old.

I stood in the doorway of the shop as she talked and looked out onto a bright September afternoon and felt that familiar itch, and the prospect of driving an hour into the country on the confused (or at least confusing) assurances of a octogenarian began to have a certain fascination. I found myself making an appointment to meet her this morning at her home about a half-hour or so north of Chelsea, Michigan.

The roads up there were, like many gravel township roads in Michigan, of variable quality. I finally found the house and parked next to the falling-down barn and a neighbor corralled the big dog who, despite the barking, was allegedly quite friendly and then I went into the house.

There were the not altogether unexpected oxygen canisters and pill bottles and the walker, and my caller cheerfully admitted to being somewhere north of 80. The walls were hung with large mid- to late-19th century portraits of forebears in carved walnut frames and one lengthy handwritten family tree that stretched back into the early 19th century. Books were stacked on the table and I was told there were more books upstairs.

The books were dispiriting–Grosset & Dunlap reprints of dreadful novels, odd volumes of home handy books, and a stack of Gene Stratton-Porter reprints held together with tape. The names penciled in the older books were also the names of various roads in the township–Wasson, Kuhn. I began to suspect I had stumbled into an old settler family’s home but found nothing that seemed to suggest that the early settlers had brought any good books with them.

I was musing on the curious instability of family libraries and had just picked up a ca. 1905 cheap subscription doorstop of popular treatment of the Russo-Japanese War that somebody would have bought from a book canvasser back in the day, when the woman saw what was in my hand and she told me, “That book was sold to my uncle by a young man who was going door to door selling books. He showed up at my uncle’s door at the end of the day and my uncle bought the book and the young man asked if he could sleep that night in my uncle’s barn. My uncle said he could not sleep in the barn, because he had a perfectly good spare bed and the young man would come have supper with them. And so the young man stayed the night and had supper with my uncle and aunt and the next day the young man came back after another day of going door to door and he stayed the night again.

“The day after that, my uncle drove him to the train station–in a buggy, you understand–and the next month when the young man came back with the books my uncle saw him trying to drag that carton of books around and told him to get into the buggy and he drove the young man around and helped him deliver his books. My aunt gave him some more food. This was in Indiana. And do you know what? That young man just gave my uncle that book. He did not take any money for it.

“My aunt was about the most Christian woman you ever saw. You could rob a bank and she would find something nice to say to you. She would never call you mean or low-down. She wasn’t my blood aunt or anything like that, you understand. She was like a mother. A foster mother. She raised me. I was what they called a state child. The state took me when I was six. I ran away when I was six from the first home they put me in but then they found me and put me in another home. I ran away again but they found me again and then they gave me to these people in Indiana when I was eight, this woman I later called my aunt. She taught me everything. She taught me that when you get 50 cents you put 25 cents into the bank. The other 25 cents you can use to buy candy and go to the movies. She was the most Christian person I know and it was because she never talked about it–she just did it. And then when I married my husband and came to live here I was his second wife. She died of cancer in 1972. All these pictures,” she gestured at the portraits, “are of her family. I was just a state brat. And I married into a family tree.

“Anyway,” she said, “there are more books upstairs.”

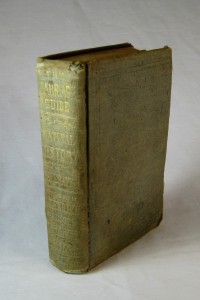

I went upstairs and found more books of little value. I saw one book in a barrister bookcase that looked like it might be of interest but the door to that case was stuck. I explored around the upstairs under the gaze of other dead family members until I found a letter opener and managed to pry open the door and found in there a thoroughly disreputable copy of a wonderful book (Frederick Hollick’s Marriage Guide, 1850) and went back downstairs and gave her all the money I had in my pocket. She thanked me and asked if she owed me anything for coming out. I said making house calls on bright September mornings like this and meeting people like her was one of the perks of the job.

I got lost on the way home (I accidentally ended up trespassing on state prison property, which according to one sign I saw was in fact a felony) but I also saw a few nice lakes and even a sign that seemed to suggest that my family might be able to go camping in a yurt.

But by then I had managed to find my way back to M-52 and headed down through Chelsea, Michigan, home of Chelsea Milling and their gleaming towers full of Jiffy cornmeal muffin mix. I’m now back in the shop and have one more book in my inventory (or had one more book; it has since sold) to show for it. I am not altogether unhappy with my job.

Frederick Hollick, M.D. The Marriage Guide, or Natural History of Generation; A Private Instructor for Married Persons and Those About to Marry, Both Male and Female . . . New York: T. W. Strong, 98 Nassau-Street; Boston: G. W. Cottrell & Co., (1850) [but ca. 1852]. 12mo, original green cloth, gilt lettering, 428, [3] pages. Color frontispiece, two color plates, numerous full-page woodcut illus. and vignettes. A reissue of the 1850 first edition, with some updated text and ads.

Physiology, sex advice, contraception, the perils of masturbation and erotomania, cannabis as an effective aphrodisiac, etc.

Hollick had been a popular Owenite lecturer on physiology, sex and likely on contraception (his ads were necessarily elliptical) and his popular Marriage Guide, “Hollick could stop depending on lecturing for his livelihood. After 1852 he devoted himself to writing popular medical books and to his growing private practice, conducted almost entirely by correspondence. About fifty letters arrived daily at his post office in Manhattan” (Brodie, Contraception and Abortion in Nineteenth-Century America).

Text here on the verso of one of the illustrations notes the success of Hollick’s lectures in 1852; the text on the verso of another illustration alludes to contraception and attacks “a remedy for this purpose, sold extensively by a person calling himself a French Professor, but who is really the husband of a noted Abortionist in New York, who has been in prison for manslaughter.” This of course is an attack on Joseph Trow, brother to the well-known Madame Restell, and whose Married Woman’s Private Medical Companion (published under the pseudonym A. M. Mauriceau) advertised “preventative powders.”

Cf. Atwater 1711 (the first edition) & Atwater 1712 (noting that copy as a ca. 1853 reissue with ads for The People’s Medical Journal for July, 1853, not present here). Binding rubbed and sunned and cocked; somewhat foxed throughout; a couple of gatherings just a trifle loose; a good, sound and somewhat disreputable copy.