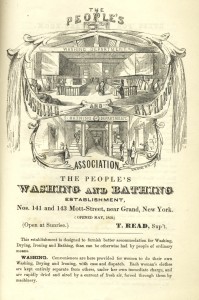

A fine view of both the washing and the bathing rooms at the People's Washing and Bathing establishment.

“Cleanliness is conducive to health,” notes an entertaining and illuminating 1853 committee report, which continues,

Who can tell, but that disease was kept from our city, the last summer, in a great degree, merely by this one establishment? Thirty-eight thousand bathed there in three months. On the 28th of May, 1300 bathed in the house. These went home refreshed, after a hard day’s work. They went home clean; their skin in good condition; their spirits exhilarated, not by a three cent drink, but by a three cent or five cent cold water (or if they choose it, warm water) bath.

(An extract from pages 6-7 of the First Annual Report of the People’s Washing and Bathing Association. 1853. New York: J. W. Harrison, Book and Job Printer.)

That such a boon might now be forgotten (for who now speaks of the People’s Washing and Bathing Association?) leads one to ask from what charitable skull burst forth this wise populist reform in 1850s New-York? For, until this era (and in fact for most years beyond), despite the occasional appearance of commercial public baths in American cities as early as the late 18th century, opportunities for the urban poor to bathe generally remained out of financial reach. (Admittedly, one was not necessarily expected to bathe with any frequency in that era.)

But as indoor plumbing became more common with the upper and middle classes, and the fad for hydropathy as the cynosure of health took hold in the 1840s and 1850s, the idea of cleanliness as a necessary adjunct to healthiness took hold, until by the mid-19th century (as historian Marilyn Thornton Williams notes in her Washing “The Great Unwashed”: Public Baths in Urban America, 1840-1920), “Among the middle class anyway, personal cleanliness ranked as a mark of moral superiority and dirtiness as a sign of degradation.” Further, she notes,

[The] 1849 cholera epidemic which ravaged American cities also produced increasing demands for cleanliness and public baths. . . . In the 1840s and later, urban reformers saw the slum not only as a threat to social stability, but also as a symptom of the moral depravity of slum dwellers. Cleanliness would produce higher moral standards in the slums (Williams, pp. 14-15).

Into this growing social movement stepped the People’s Washing and Bathing Association, an organization whose name might very well stand at the zenith of grandiose names that littered the firmament of antebellum reform. The association itself was the product of a reforming association, having been created in 1851 by the New York Association for Improving the Condition of the Poor; this specially dedicated bathing association was apparently created to rush in where the city of New York feared to tread, even in the wake of the city’s own comprehensive 1849 report of its Special Committee on Public Baths, which recommended the construction of public baths.

Thus did the People’s Washing and Bathing Association purchase land on Mott Street in 1851 and erect the fine brick building that opened to the public on June 1, 1852, where it offered public bathing and public laundry facilities to the all and sundry. This report (evidently the only issue published) is rich in detail and includes a woodcut view of the Washing and the Bathing departments, statistics, the rules of the establishment, and various endorsements of the advantages to the public weal,

Names can be given of wash-women that have earned $10 per week over all working expenses, working, on an average, less than eight hours a day. The spacious Swimming-Baths for males and females, afford capital places for Boys to learn to swim, without danger, and Girls also, to whom, in these days of disasters, the Art of Swimming may be equally necessary.

This report would seem to suggest that the baths were available in summer and winter alike (Williams claims they were open only in the summer), though Williams is likely correct that even its modest cost to sers put it out of the reach of many of the poor, and that this was largely responsible for the shuttering of this social experiment in 1861.

Suggestive too of the currents of reform, given the contemporary passage of the “Maine Law” and its perhaps evocative temperance overtones that extol the merits of water, this copy with an in inscription at the head of the front wrapper, “With the Regards of Elb. Gerry,” likely that of the grandson of the Declaration signer namesake, this Gerry (1813-1886) a member of Congress from Maine between 1849 and 1851.

This uncommon and ephemeral report has since been snatched up by a discerning institution; we leave its description for the record:

People’s Washing and Bathing Association. The First Annual Report of the People’s Washing and Bathing Association. 1853. New York: J. W. Harrison, Book and Job Printer, 1853. Original printed yellow wrappers, 20 pages. Illus. Printing flaw to the first page of text (but legible). Wrappers somewhat soiled; title page and first leaf somewhat spotted, stained and foxed; a good copy. First edition.