In Ann Arbor a couple of summers ago, wherever you went it seemed like you ran into the tag for a graffiti artist who went by DUCK. The tag was pretty simple—a little pseudo-diacritic and the occasional stylized picture of a duck were about all you got in addition to the script—and despite my secure lock since entering my forties on the title of Number One Uptight Square (Washtenaw County division), I was prompted by the elegant diligence of the work of DUCK to take a pleasant (if mild and perhaps covert) interest in tagging or writing. Finding fresh evidence of DUCK’s labors was inevitably a source of delight (of course I never had to scrub it off of anything) and a few examples linger unscrubbed and unscathed on the edges of downtown.

But in the history of American graffiti, back before the dawn of the modern era of tagging—way, way back before DUCK, and back before the early attention given to TAKI 183 in New York or to Philadelphia’s CORNBREAD (who, in response to a newspaper report of his death, snuck into the zoo to spray paint the message “Cornbread Lives” on both sides of an elephant), or even back before the invention of spray paint and before the ubiquitous Kilroy of World War II—one would see early examples of a sort of tagging roll past on the rails, the once ubiquitous chalked graffiti on the sides of American boxcars.

Hobo codes had of course long been in use on railroad cars and all sorts of other places to pass along information to itinerant gentlemen of the road, but while something like the hobo’s stylized cat (“kind lady”) is pretty nifty, it doesn’t say much about the person who wrote it. The brief but illuminating chapter on “Monikers” in Roger Gastman and Caleb Neelon’s recent magnificent doorstop History of American Graffiti (Harper Design, 2010) notes,

Decades before spray paint was even invented, hobos and railroad men left their marks on freight trains. Called monikers . . . these were simple chalk line signatures of a nickname along with a single icon, caricature, or symbol emblematic of the freedom and fantasy of riding the rails.

(That last part seems like maybe a little bit of a stretch—how much was emblematic of the freedom and fantasy of riding the rails, and how much of the boxcar art was a response to the tedium of hustling freight?)

But Gastman and Neelon trace the evolution of the moniker back through hobo codes to Civil War veterans riding the rails (the ex-soldiers employed variations of codes used in the war), and then the evolution of monikers among railroad workers. They note,

One of the most iconic boxcar artists of the Depression years was BOZO TEXINO, who was known for his simple chalk portrait of a man wearing a ten-gallon hat and smoking a pipe. Many thought the illustration was the work of a hobo, but in July 1939, Railroad Magazine revealed that BOZO TEXINO was J. H. McKinley, a Texan who worked for the Missouri Pacific Railroad.

(Gastman and Neelon point out that popular monikers were often revived, viz. GRANDPA BOZO TEXINO, who later chalked up some 350,000 examples of his own variation on the original and who is quoted in this account as saying “I had one boss who told me to stop markin’ them cars. Sure enough I told him to go fly his damn kite.”)

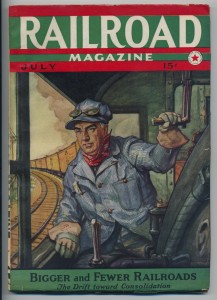

A copy of that issue of this entertaining pulp Railroad Magazine has recently come to hand, and the bookseller in me would suggest that the article “Boxcar Art” should be necessary reading for anybody interested in the evolution of American graffiti art. One of the great pleasures of this job is the chance to dig up material that swings a Wiffle bat upside the notion that contemporary culture has some sort of lock on individual expression or just plain weirdness. For every man in a gray flannel suit (or its non-anachronistic functional equivalent) there’s also a guy out there with a stick of chalk willing to tell a boss to go fly his damn kite, and our doddering Republic is perhaps a bit sloppier around the edges but I think all the better for it.

A copy of that issue of this entertaining pulp Railroad Magazine has recently come to hand, and the bookseller in me would suggest that the article “Boxcar Art” should be necessary reading for anybody interested in the evolution of American graffiti art. One of the great pleasures of this job is the chance to dig up material that swings a Wiffle bat upside the notion that contemporary culture has some sort of lock on individual expression or just plain weirdness. For every man in a gray flannel suit (or its non-anachronistic functional equivalent) there’s also a guy out there with a stick of chalk willing to tell a boss to go fly his damn kite, and our doddering Republic is perhaps a bit sloppier around the edges but I think all the better for it.

Our copy has since found a home more congenial than the shelves of this bookselling concern. Here’s the original description:

[Graffiti]. (McKinley, J. H.). Arthur W. Hecox. “Boxcar Art.” [In:] Railroad Magazine. Vol. XXVI, No. 2. July, 1939. New York: Frank A. Munsey Company, 1939. 8vo, original color pictorial wrappers, 144 pages on pulp, illus. First edition.

Incunabula tagging (or writing, for graffiti purists), a three-page article on early graffiti artists, a survey of the artwork and stylized signatures of the hobos and railroad workers who marked up freight cars with pictures and messages in text (such as the once ubiquitous J.B. King Esquire); this article is notable for including the identity of Bozo Texino, whose “familiar caricature shows him smoking a long pipe and wearing a ten-gallon cowboy hat adorned with the lone star of Texas. The original of this crude portrait is a tall, handsome Texan. . . . Skeptics have questioned whether or not Bozo Texino is a real person. I can assure you that he is, just as real as President Roosevelt. His name is J. H. McKinley.” (The caption to the photo of McKinley that accompanies the text notes him putting his trademark on “One of the Quarter-Million or So Boxcars Which He Has Adorned in the Past Twenty Years–Not Mo. P. Cars [his employer Missouri Pacific] However; There’s a Rule Against It.” (The photo is credited to the San Antonio Light, suggesting McKinley’s identity had been earlier revealed, at least on a local level.) Hecox glances at political and religious messages, obscene doggerel, and even the “queerest type of free advertising [which] is the urging of the public to correspond with the person who has written his or her name and address on the car. It is more than likely that lonely scribblers of both sexes have obtained sweethearts by this method; but if so, no authentic instance has ever been brought to my attention.” Some slight wear to the wrappers; cheap paper somewhat browned; a very good copy.