Much has been made of late about the fact that the Internet is killing off the traditional publishing business (and of course its hapless trade cousin, the book store). I would suggest that the publication and peddling of books has always had its hazards, the foremost and most pedestrian of course being the need to undam diverse pecuniary streams into which the publisher or bookseller might dip to keep the concern at the very least staggering along.

(One rather happy if digressive example of such resourcefulness that occurs to me here is that of the late 18th century chapbook publisher Henry Lemoine, who despite being perhaps the foremost English peddler of cheap literature and pamphlets tailored to the “predilections and the common bent of the popular mind” [Federer, Yorkshire Chapbooks, 1889, as quoted by Roy Beardon-White] was constrained by necessity early in his career to also offer his customers “medicines and cure-alls. These cure-alls included a concoction called ‘Bug-water,’ the formula for which Lemoine supposedly received from Dr. Thomas Marryat” [Roy Beardon-White, “A History of Guilty Pleasure: Chapbooks and the Lemoines,” Papers of the Bibliographic Society of America 103:3 (2009), page 296]. As Beardon-White notes of Lemoine, “Booksellers, as with most street vendors, focused more on surviving than in staying within arbitrary boundaries of their craft.”)

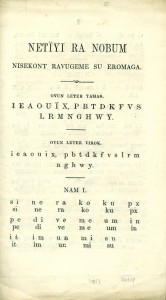

But it was literal survival that must have been from time to time on the mind of one publisher of cheap children’s literature of a sort, as embodied in an example that has recently come across my desk here at my own sometimes staggering bookselling concern. In 1864, the Mission Press on the island of Aneityum (the southernmost island in the chain once known as the New Hebrides and now more properly of course the nation of Vanuatu) published  this little stitched 8-page primer with lessons on the days of the month and a selection of short religious texts for use on the nearby island of Erromango (also somewhat confusingly referred to in various sources as Erromanga, the spelling I somewhat arbitrarily prefer).

this little stitched 8-page primer with lessons on the days of the month and a selection of short religious texts for use on the nearby island of Erromango (also somewhat confusingly referred to in various sources as Erromanga, the spelling I somewhat arbitrarily prefer).

Printing had come to the New Hebrides with the arrival on Aneityum in 1848 of missionary John Geddie and a secondhand Canadian hand press. After Geddie managed to secure a newer press in 1853 he transferred his original press to Erromanga to help his fellow missionary, Rev. George N. Gordon, with his efforts to translate and publish works in the languages of Erromanga.

Gordon was not the first to try his hand at sowing the Gospel among the natives of the island, having been preceded in his work by “the Apostle of the New Hebrides,” Rev. John Williams, who arrived on Erromanga in 1839 along with sailor James Harris. (Harris was evidently considering a career change from sailor to the ministry, no doubt hoping that the clerical life would provide fewer challenges to compare with the workaday hazards of climbing out on a yard in a squall to reef the sails.)

But unhappily enough for the dreams of both, Williams and Harris were set upon as they scouted for a likely location for a mission station, killed by the residents of the island and eaten by their prospective flock. Never ones to give up easily, especially when making these decisions from a safe remove back in England, for a number of years thereafter the London Missionary Society sent Christian Samoans and Roratongans to Erromanga to carry on the missionary efforts, but they were variously killed outright or starved out by the native population.

Gordon, who arrived on the island with his wife in 1855, for a time had better luck than his earlier brethren. According to John Ferguson’s Bibliography of the New Hebrides and a History of the Mission Press (Sydney, 1917-1918), Gordon in 1859 even managed to run off a Catechism (or in the native language, Netiyi Tagkeli) on his third-hand Erromanga press, before he ended up taking the blame for bringing a measles epidemic to the island in 1861 and he and his wife were killed. No further evidence of Erromanga printing of the period seems to exist and it seems likely the press fell into disuse after the Gordons’ deaths.

Presbyterians being ever a hardy bunch, the lamented Gordon’s brother James Gordon arrived on Erromanga in 1864 to take up the call, even though his mission field was now popularly known as “the Martyr Isle.” James Gordon carried on the translation and publishing work of his brother–though according to Ferguson he published most of his work in Sydney. (Indeed, of primers in the language of Erromanga, Ferguson notes in the first entry in his bibliographical checklist of “Translations in the Language of Erromanga” the production in 1852 of “A primer in Erromangan. Printed by the Rev. Geddie at the Aneityum Mission Press, to assist the Samoan native teachers in their work. No copy known.”) It seems likely of course that the arrival of James Gordon in 1864 had revitalized the Erromangan project (and indeed, Ferguson notes a 108-page translation of Luke issued by the Aneityum press that year) but Ferguson does not note this title.

Thus did the second Rev. Gordon carry on his work, and by all reports he met with some success–until another bout of measles swept across the island in 1872 and he became the latest missionary to take the blame for the inevitable misfortunes of colonialism and the natives happily handed him the martyr’s palm.

Subsequent Erromangan primers (with Catechisms included, evidently not included in this 1864 edition) were published in 1867, and then in 1878 and 1881 for the use of the missionary H. A. Robinson, who managed the trick of surviving long enough to publish an account of life on the island, Erromanga: The Martyr Isle (London, 1902). (Other accounts of the island appear to draw in part from this source.)

This unassuming but nifty little pamphlet has since been sold; here is an excerpt from its original catalogue description:

[Rev. James D. Gordon?]. Netiyi Ra Nobum Nisekont Ravugeme Su Eromaga . [Colophon:] Aneityum: Mission Press, 1864. 8vo, unbound pamphlet, [8] pages. Second edition? First edition thus?

A rare edition of this primer, with lessons on the days of the month and a few short Bible extracts and the Lord’s Prayer, in a language of the southern Vanuatu island of Erromanga, and an early surviving title in the Erromanga dialect printed at the Aneityum Mission Press, this title not noted in Ferguson’s Bibliography of the New Hebrides and a History of the Mission Press. This 1864 primer, with the uncommon mission press imprint, is located today at two locations (per OCLC): Indiana University and the State Library of New South Wales. The island evidently once had four dialects (of which three are extinct); fewer than 2000 speakers remain.