Jay Platt of the West Side Book Shop. Photo by Myra Klarman.

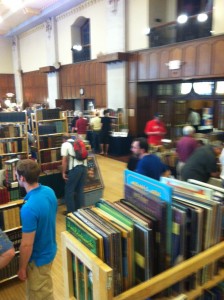

So we had the 34th (or maybe 36th?) Ann Arbor Antiquarian Book Fair last Sunday. They held it as has long been the case at the Michigan Union–one of the finest examples of a funky high Gothic-revival utilitarian space this side of Hyde Park–on the campus of the University of Michigan.

(The freight elevator of the Michigan Union is also suitably Gothic–in that it is as creaky as the plot of a Monk Lewis tale–which is why you see more and more booksellers with hand trucks sneaking up the civilian elevators over by the Wendy’s with every passing year.)

This was the 14th year that I’ve exhibited at the fair (and the 13th straight year that I’ve loaded in and out using the elevator over by the Wendy’s) and as usual the fair had about 40 dealers and a pretty amazing ratio of good stock to dreadful junk for a fair of its size.

I’ve always enjoyed exhibiting at the Ann Arbor Book Fair and have as I’ve reached more mature years begun to wonder how Jay Platt, the fair organizer (and owner of Ann Arbor’s West Side Books) manages to pull off the trick of luring a bunch of good dealers into town for a fair.

Those unfamiliar with the rare book trade might be forgiven for thinking that a book fair is a series a moderately boozy meals into which a brief period of nominal bookselling has been forcibly wedged. But before you can plausibly spend a weekend sitting around the groaning board with your colleagues, you have to insure that folks will come in the door to attend the book fair, else the members of the book trade will lack sufficient motivation to leave their lonely rooms where they sit and catalogue their stock to instead invest the time and money to travel to Ann Arbor to stand around in a room with other booksellers for six hours on a Sunday. (One advantage the Michigan Union’s venue has over some anonymous hotel ballroom is the well-lighted elegance; at the end of a slow day of sales at Ann Arbor, you feel less of the crushing anomie inherent in the fluorescent-lit carpeted hell of a Holiday Inn somewhere.)

Some folks, coming through doors.

So how do you insure folks will come through those doors on a Sunday to browse and perhaps even purchase your books come the day of the book fair? This year Jay decided to hire the local photographer Myra Klarman to come snap some promotional photos of the fair, and Myra–being the community-minded dynamo that she is–took the book fair in hand and began to help promote the event. (Myra’s photos coming soon; unless otherwise noted, the snaps here are the author’s own.)

When Myra canvassed some local booksellers to tell her what this whole book fair thing was all about, I wrote to her,

One of the things going on with the Ann Arbor Book Fair (and book fairs in general) is the progressive graying of the demographic. Younger people (and in book terms that means people in their 30s and 40s) seem less engaged with in-person browsing and buying than the Boomers. The gray-bearded guy who goes from booth to booth asking “Anything relating to the War of 1812?” We’ve got that demographic locked up; retired obsessive types are our traditional customers.

What I think we want to avoid visually when promoting the fair is a stack of leather-bound books with a pair of wire-rimmed glasses on top of the stack (the hoariest image in bookselling) as my peculiar constitution is such that whenever I see this image it fills me with rage.

But what if we could get into the head of somebody who might be deciding whether to make a weekend of visiting Ann Arbor from Toledo or Chicago, or who locally would maybe be going to UMMA or to Sweetwaters on a Sunday and who might have once gone to Borders[1] on a Sunday to poke around, say instead, “Hey, I can go check out some cool stuff at the book fair!”

When a book fair is going great, esp. in a beautiful room like the Michigan Union Ballroom and a relatively dense accumulation of a small number of dealers, it can feel like a good gallery opening — crowds excited and seeing stuff they didn’t expect they would see. The personality of the fair might sometimes be like the cool uncle who blows in from out of town when you’re in high school in a small town and he takes you to an obscure ethnic restaurant for the first time and teaches you about the Dadaists. You say “Oh, wow!” and you want to learn more.

Myra turned me on to this new thing called “Facebook” that she suggested might make a good venue for getting out word about the fair to this coveted younger demographic. So with Jay’s permission I began a Facebook page with an eye toward promoting the fair as a groovy place to see cool stuff[2].

(This of course is the sleight-of-hand involved in nearly any commercial transaction but maybe most especially in the sale of rare books, since most booksellers aren’t dapper uncles who show up in a Karmann Ghia while smoking a meerschaum pipe but are instead moderately lumpy folks with sore lower backs and minivans or perhaps a Subaru who stagger over to a venue before dawn to load unwieldy boxes into yet another ballroom for a show.)

Lorne Bair and Brian Cassidy hanging out before dinner. The empty parking space behind them would soon be occupied by Adam Davis, who won the long-distance prize from coming in from Portland (Oregon).

But speaking of the groovy-uncles-from-out-of-town types, the Saturday night before the fair my wife Betsy Davis, my daughter and I had colleagues Lorne Bair, Brian Cassidy, and Adam Davis of Division Leap over for dinner at our house. (My dad was also in attendance from Normal, Illinois.) May in Ann Arbor can put heart into the most jaded rust-belt resident and pleasant conversation and Spring evenings in Washtenaw county go far to conjure hints of our prelapsarian age. (Or perhaps the cocktails were responsible for the glimpses of Edenic splendor out on our front lawn.)

The next morning I awoke at 5am and decided to head over to the book fair. I was the second person to arrive (behind Larry Van De Carr of Booklegger’s Books of Chicago; Larry emerged half-asleep from the back of his van around 6am in his stocking feet and I realized I had some ways to go before I was truly an intrepid book fair exhibitor). The morning was limpid and filled with late Spring birdsong, so uncharacteristically pastoral that it made me reconsider spending the day in a ballroom surrounded by paper.

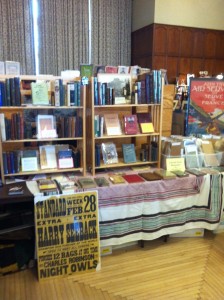

The booth at 6am. I am tempted to go with this stripped-down approach.

But the excitement of the fair soon took hold and I was set up by 9am with my minimal display and was ready to start scouting the book fair before doors opened.

The fair opened at 11am and we had a steady if slow stream of folks through the fair until it closed at 5pm. I saw plenty of folks in their teens and twenties and hope it was enough to plant the seed for them of the romance of book buying. (The collecting as such is to my mind secondary; the moment of discovery provides the biggest excitement of this whole enterprise–though discovery can come while scouting and finding book, or getting it home and figuring out what it is, or in finding out that someone

Despite my laziness I ended up unloading the car and setting up a booth.

is willing to hand you money or a note of hand in exchange for the book in the first place, capitalism being of course the weirdest unexamined aspect to this whole undertaking.)

Despite having leveraged social media, attendance was down this year–somewhere south of 500 paying customers–but I choose to consider this too small a sample size from which to draw too many conclusions.

After the fair was a long fine evening of dinner and conversation and more dinner and more conversation at Zola with a few dealers and civilians and a rogue local curator. This was another extracurricular highlight not directly associated with the fair.

Brian Cassidy, Adam Davis, and Lorne Bair scout Garrett Scott, Bookseller.

Then after dinner and a couple hours of sleep, my shop got a visit from Messrs. Bair, B-Cass and Division Leap. They managed to find a few things amid the chaos and then began to wind their way back toward their respective far-flung home bases. The weekend was something resembling a success even when the measure in dollars was perhaps modest. These sorts of fairs are a kind of advertising for the tangible personality of the trade, and as much as I hate the romance of old books (whenever I hear the phrase “dusty tomes” I reach for my revolver) I sure love this stuff and the people associated with it and hope I can show other folks how they might love it too.

Anyway, I did pick up a stack of things during the fair. (Nothing spectacular but plenty of interest.)

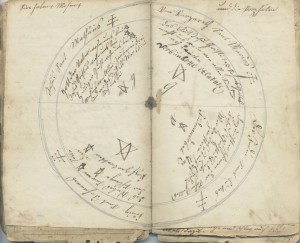

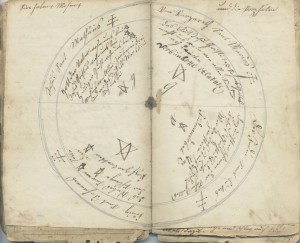

Being kind of stupid makes the world more interesting. I will be crushed when I find out this manuscript is something prosaic.

I’ve decided after one of these finds that I will teach myself German and then teach myself 19th century German-American script so I can better figure out this strange manuscript journal that seems to have something to do with mystic formulae (the Sator Square pops up with some frequency).

Another rather charming piece from the always interesting A. England of Hillsdale, Mich. were these two early 20th century images of a man in drag (see below). What will I do with them? With any luck I will sell them and then go out and find some more stuff and have some more dinners and the trade will (despite all evidence to the contrary) still be alive and maybe even something more than just the exchange of information.

—

[1] An example of something we used to have downtown called a “book store.”

[2] Back in the old days (until the Summer of 2009) our town had a daily newspaper, a medium that used paper and ink to spread detailed information about University of Michigan football throughout the community but that also, according to Jay Platt, apparently just let you wander into the newspaper office as a book fair promoter to say “Hey, we’ve got a book fair” and they would pull a reporter off the Elvis Grbac beat and send her over to write up a nice article about the fair and the book-loving populace would throng through the gates and the great chain of bibliophilia and newspaper reading continued its now archaic symbiotic dance.

[3] Ever since I’ve done the fair, not only were the dealers setting up from about 6am and buying books from each other, they were more than likely trying to buy books from the duplicates and out-of-scope sale table set up by the William L. Clements Library, where the Clements would take various miscellaneous books out of cartons and put them on the tables but then tell the booksellers that they could look at the books but not actually touch them until the doors opened to the public at 11am and booksellers needing of course to pay the rent and utilities and maybe even spring for an occasional haircut (despite appearances) would begin sometime around 9:30 or so to stand casually near the Clements’ table and box each other out and splay their elbows protectively as they eyed the table and tried to read the spines and size up the stock until the doors opened at 11am and then the booksellers got all Jack London sled dog on those books and these poor curators who had gone to graduate school and become scholars and ended up at one of the nation’s foremost repositories of 18th and 19th century Americana would be forced to wade into the scrum to bust up fights between dealers grappling over stock.

Timid soul that I am, I generally hung back from the fray, and as I watched this all unfold I could see in the eyes of any given curator as she waded into this baying pack of commercial bibliophilia the thought forming in her mind that she might never respond to a quote of material from any bookseller again, ever; it was thus I decided to take the prudent course and make my nut elsewhere.

(The Clements has latterly in the interests perhaps of public safety let the dealers get an earlier crack at the offerings and is in fact putting out fewer books each year and otherwise done what it can to get out of the used book business, which is not surprising as many used booksellers have decided to get out of the used book business for many of the same reasons as the Clements: you have to work hard and it doesn’t pay very well.)

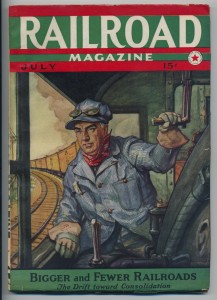

Evidence suggests his name is "Rex."

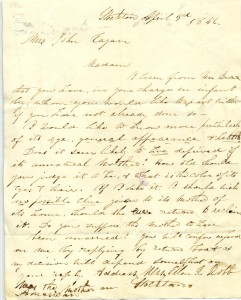

For the past number of years I’ve been somewhat haphazardly accumulating American letters and manuscript material from 1856 with a view toward assembling a collection representative of the depth and breadth of American concerns in a year that sometimes gets forgotten as a transitional time, what with some of the shine beginning to come off of the Gold Rush, one of our worst presidents preparing for his election run, and the nation getting itself wound up for the Civil War–who wants to dwell on a year like this?

For the past number of years I’ve been somewhat haphazardly accumulating American letters and manuscript material from 1856 with a view toward assembling a collection representative of the depth and breadth of American concerns in a year that sometimes gets forgotten as a transitional time, what with some of the shine beginning to come off of the Gold Rush, one of our worst presidents preparing for his election run, and the nation getting itself wound up for the Civil War–who wants to dwell on a year like this?